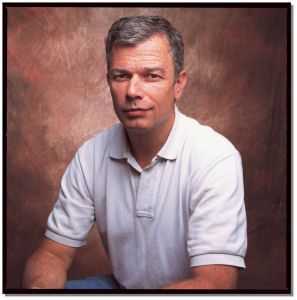

Intel VP Dadi Perlmutter: Is the company really "no longer a chipmaker?"

Haifa (Israel) - In his 25 years with Intel, Dadi (David) Perlmutter has been responsible for developing some of his company's most innovative technologies. He worked with math co-processors in the pre-486 era, the first-generation Pentium, and the MMX technology which launched the era of the multimedia PC. In the late '90s, his team developed Timna, an integrated, all-purpose CPU concept which the company later cancelled during the shift toward NetBurst architecture. In recent years, he has led the development of the Centrino platform and the Pentium M, and is presently in charge of the future Merom micro-architecture platform.

Yet he is nothing like you'd expect a corporate executive to be. You might have a hard time catching Perlmutter acting formal, wearing a suit or a tie, or talking about himself. Although he is now the manager director of Intel's Mobility Group, and has been an Intel vice president for many years, he is far from being a sweet-talker, and it's clear success hasn't made him less humble than he always was.

TG Daily: Dadi, how does it feel to lead the development of Intel's fastest growing business segment?

Dadi Perlmutter: Well, it feels good. It's an area we're working on for many years now in Intel, and in the development center in Haifa specifically. A large part of the ideas, both in technology issues and in business issues, came from our group. So it definitely feels good. There's a sense of achievement and there's the feeling we still have a lot of things we can do.

TG Daily: In the press conference prior to IDF Israel last week, you were asked about integrating features into silicon, and briefly stated that such design have it's limitations. I could not help thinking about Timna. Its cancellation was kind of traumatic, wasn't it?

Perlmutter: "Traumatic" is a strong word, but such experience does effect people. Although I must say we learned a lot from it - from the mistakes we made but also from the good things we achieved, which we also brought with us into the development of Banias. A large part of our knowledge in low-voltage processing came from the Timna project, so it's not as if everything we did there went down the drain.

TG Daily: What are the advantages and disadvantages of using an Israeli team in developing a future micro-architecture?

Stay On the Cutting Edge: Get the Tom's Hardware Newsletter

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Perlmutter: First of all, there are excellent engineers in Israel. They have good education and knowledge and they have the drive to make things differently. There's lots of creativity and ambition to think of things others didn't, and go beyond what you're expected to do. Sometimes this means very hard work, but many times this is what helps you achieve a better outcome than what you asked for, which is exactly what is needed in this area. This, by the way, is a thing I think we have in common with a lot of Israeli companies.

There are also some thinks we lack. The American teams are better when it comes to discipline and organizational skills, and we try to learn from them.

TG Daily: What is your reason for not including support for 64-bit technology in Yonah? Why is it going to be supported only in Meron?

Perlmutter: Like everything in technology or life, it is all a matter of timing. Integrating unneeded features into a processor means a waste of power consumption. Our assumption was, and still is, that 64-bit extensions are not the most important thing required from a processor, not even in the beginning of 2006. We believe this will change with Windows Vista, when applications start migrating to 64-bit, and we want to be ready then, and not a minute earlier.

TG Daily: So it would be accurate, then, to state you simply didn't want to break Yonah's power envelope?

Perlmutter: Yes. A very important aspect of such a development is carefully examining the trade offs. This is not only about what to include, but also about what not to include. When you put in more features, it costs you in money and in power.

TG Daily: During the IDF Israel conference, you and other executives stated time and again what looked like a pre-dictated marketing message. Like saying Intel is "no longer a chipmaker" for example. This is something you didn't do in the past, right?

Perlmutter: Well, I was asked the same question in China. We certainly are a chipmaker. The message was not that Intel stopped being a chipmaker, but rather that Intel is not only a chipmaker anymore.

It's no secret Intel is in the middle of a strategic change. That's a move driven by our CEO Paul Otellini, who is pushing a solution-oriented approach. Our platforms now offer a different added-value, and this should be explained. In the past, we used to talk about clock-rates, buses and cache, but with time we realized most people weren't that fascinated with such information. And it changed not only the way we speak, but also the way we think and develop.

Fascinating technology is interesting for professional users. When approaching wider audiences, the things you should deal with are pretty different. We came to the conclusion that there are four things that mobile users look for in their notebooks. They want it to have performance, just like with their desktops; they want longer battery life; they want it to be slim and easy to carry; and they want it to have a wireless connection.

TG Daily: What are your technical goals for different market segments, in terms of power consumption?

Perlmutter: We're aiming for 30-35 W in Thin & Light configurations, and around 10-15 W in lower configurations. For desktop and server platforms our goal is around 65-70 W. Of course there will also be lower values when it comes to mobile platforms, or fan-less devices like EPCs. The latter will be sitting in your living room, so you would probably like them to be quite and have no fans.

Today's Ultra Low Voltage products have a power envelope of 5 W. In 2008 we will have UMPCs with power consumption of 3-4 W.

TG Daily: How far are we today from hitting lithography bottom? And what will you do when we get there?

Perlmutter: This is a good question, for which I can't really say I have a good answer. Current miniaturization will probably progress for at least until 2015. After that we shall probably have to use other solutions, which we are already looking for, naturally.

Most Popular