UK company shoots a 1000-degree furnace into space to study off-world chip manufacturing — semiconductors made in space could be 'up to 4,000 times purer' than Earthly equivalents

One small step for chips, one giant leap for a lack of impurities.

A team from Cardiff, Wales, is experimenting with the feasibility of building semiconductors in space, and its most recent success is another step forward towards its goal. According to the BBC, Space Forge’s microwave-sized furnace has been switched on in space and has reached 1,000°C (1,832°F) — one of the most important parts of the manufacturing process that the company needs to validate in space.

“This is so important because it’s one of the core ingredients that we need for our in-space manufacturing process,” Payload Operations Lead Veronica Vera told the BBC. “So being able to demonstrate this is amazing.” Semiconductor manufacturing is a costly and labor-intensive endeavor on Earth, and while putting it in orbit might seem far more complicated, making chips in space offers some theoretical advantages. For example, microgravity conditions would help the atoms in semiconductors line up perfectly, while the lack of an atmosphere would also reduce the chance of contaminants affecting the wafer.

These two things would help reduce imperfections in the final wafer output, resulting in a much more efficient fab. “The work that we’re doing now is allowing us to create semiconductors up to 4,000 times purer in space than we can currently make here today,” Space Forge CEO Josh Western told the publication. “This sort of semiconductor would go on to be in the 5G tower in which you get your mobile phone signal, it’s going to be in the car charger you plug an EV into, it’s going to be in the latest planes.”

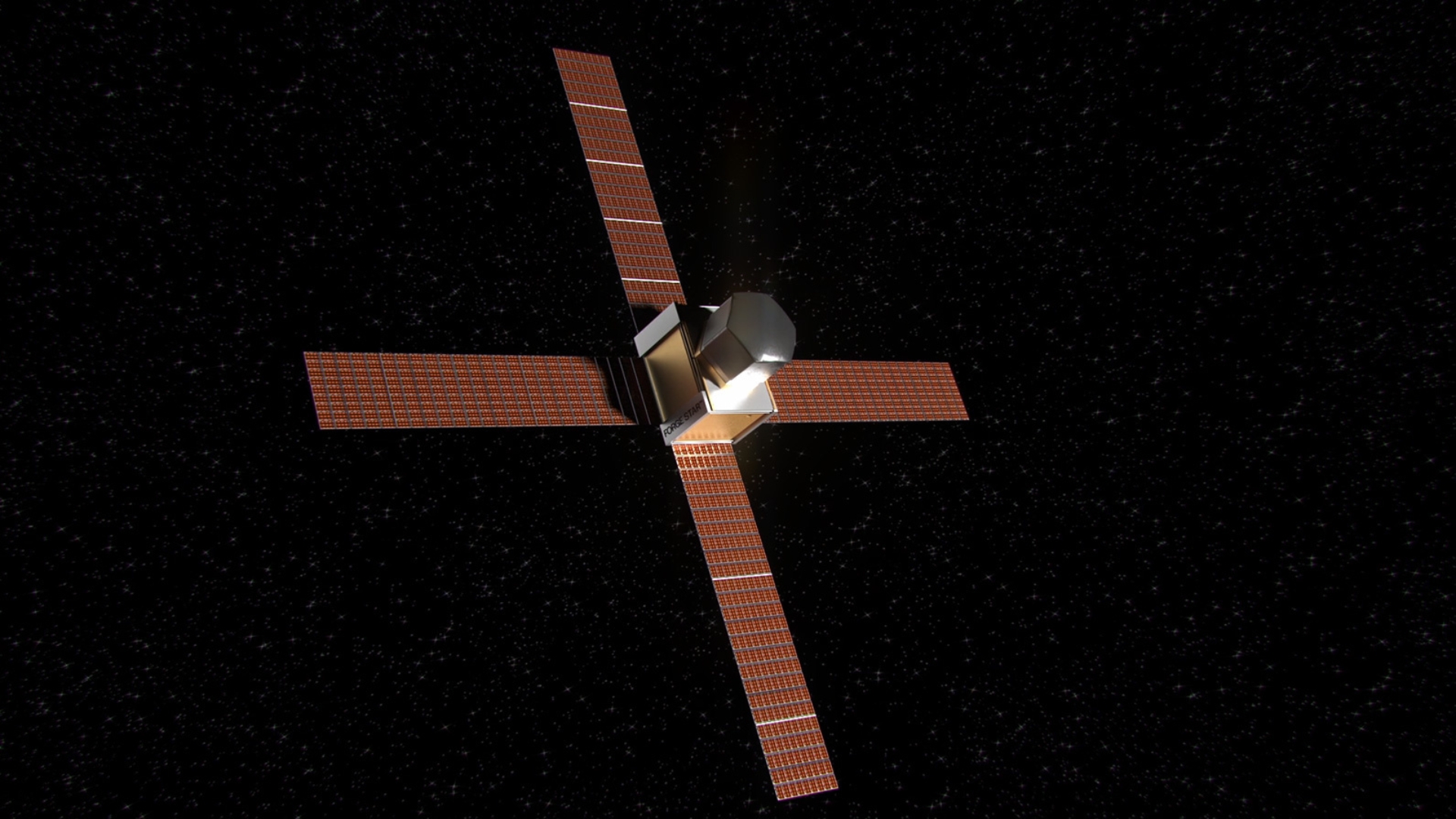

Space Forge launched its first satellite in June 2025, hitching a ride on the SpaceX Transporter-14 rideshare mission. However, it still took the company several months before it finally succeeded in turning on its furnace, showing how complicated this project can get. Nevertheless, this advancement is quite promising, with Space Forge planning to build a bigger space factory with the capacity to output 10,000 chips. Aside from that, it also needs to work on a way to bring the finished products back to the surface. Other companies are also experimenting with orbital fabs, with U.S. startup Besxar planning to send “Fabships” into space on Falcon 9 booster rockets.

Putting semiconductor manufacturing in space could help reduce the massive amounts of power and water that these processes require from our resources while also outputting more wafers with fewer impurities. However, we also have to consider the huge environmental impact of launching multiple rockets per day just to deliver the raw materials and pick up the finished products from orbit.

Follow Tom's Hardware on Google News, or add us as a preferred source, to get our latest news, analysis, & reviews in your feeds.

Get Tom's Hardware's best news and in-depth reviews, straight to your inbox.

Jowi Morales is a tech enthusiast with years of experience working in the industry. He’s been writing with several tech publications since 2021, where he’s been interested in tech hardware and consumer electronics.

-

cyrusfox Sounds wildly optimistic. Even if the physics checks out, how do you realistically supply the tools, materials, power, and maintenance in orbit at any scale that matters economically?Reply -

thisisaname This is a technical close to making chips in space as a candle is to a space laser. Interesting but they have very far to go.Reply -

bit_user Reply

Those are all engineering problems. Hard ones, but the first step is figuring out whether space truly offers advantages not available in terrestrial manufacturing. If not, then we can stop right here. If so, then the next step is to figure out all the issues around performing the full chipmaking process (or at least all of the stages that need to happen in orbit) and the logistics + scale-up problems you mention.cyrusfox said:Sounds wildly optimistic. Even if the physics checks out, how do you realistically supply the tools, materials, power, and maintenance in orbit at any scale that matters economically?

Someone mentioned that an Orbital Skyhook is much more practical than a space elevator and still a more efficient way to get stuff into orbit than launching every payload with all the propellant needed to get it into orbit.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skyhook_(structure)

The problem with fully self-propelled launch vehicles is that the propellant needed for that last leg of the journey adds weight and must itself be lifted, as well as the additional fuel tank capacity needed to hold it. So, the benefits of launching to a suborbital altitude are nonlinear. -

George³ So, in reality, nothing has been achieved and the theoretical maximum results will probably remain on paper forever? Heating devices are not like they were first launched into space. There are hardly any spacecraft without systems for maintaining the temperature environment, including heating, because it hardly heats up to 1000 degrees, although rheotans (or their modern successors in the role of heating elements) can reach hundreds of degrees. How do they deal with defects caused by cosmic radiation in the manufacturing process. Oh, wait, in fact, they didn't start a manufacturing process at all, they just heated up a small furnace. What a pity that you can't just heat a little silicon in a furnace and turn it into a modern chip with just this processing.Reply

Ps. Small answer from Gemini LLM:

The use of furnaces for heating materials in space has a long history dating back to the 1970s. While the article highlights semiconductor production by the British company Space Forge, high-temperature processing technology in orbit has been applied dozens, if not hundreds, of times before.

Here is a summary of the types and quantities of furnaces launched to space stations prior to this mission:

1. International Space Station (ISS)Multiple high-temperature furnaces have operated on the ISS, some reaching temperatures significantly higher than the 1000°C mentioned in the article:

Electromagnetic Levitator (EML): Developed by ESA, this furnace can heat metals up to 2100°C. It allows for containerless melting (via levitation), which is key to achieving the material purity mentioned.

Materials Science Laboratory (MSL): Includes modules like the Low Gradient Furnace (LGF) and the Solidification and Quenching Furnace (SQF), which reach up to 1400°C.

Kobairo Rack (Gradient Heating Furnace - GHF): A Japanese furnace in the "Kibo" module designed for high-quality crystal growth at temperatures up to 1600°C.

SUBSA and PFMI: Older furnaces (dating back to 2002) operating around 850°C for semiconductor research.2. Tiangong (Chinese Space Station)China has achieved significant records in this field in recent years:

Containerless Materials Processing Cabinet: Between 2024 and 2025, Chinese scientists reported heating tungsten alloys to over 3100°C (the highest temperature ever achieved in orbit).

High-Temperature Materials Science Experiment Rack: The station features specialized infrastructure for stable, high-temperature material science research.3. Historical Stations (Mir, Salyut, and Skylab)Mir and Salyut (USSR): Between 1980 and 1991, over 500 experiments were conducted on Soviet stations using furnaces such as "Kristall," "Splav," and "Korund." These were used to melt semiconductors, optical materials, and superconductors, often at temperatures exceeding 1000°C.

Skylab (USA): As early as 1973, Skylab housed a multipurpose furnace (M518) that reached 1000°C to study crystal growth and metal alloys.SummaryWhile it is difficult to provide an exact "count" of individual devices (due to many interchangeable modules and upgrades), over 20 major types of large-scale furnace systems have been sent into space throughout history, performing thousands of individual heating cycles.

The Space Forge experiment is significant not because it is the first, but because it focuses on commercial and scalable manufacturing (via the returnable ForgeStar satellite), whereas previous furnaces on space stations were primarily used for fundamental scientific research.

Would you like me to look for more technical details on how the ForgeStar satellite's return mechanism compares to how samples are brought back from the ISS? -

LordVile Reply

It’s not really an engineering problem it’s an accounting problem. If you do find a way to power it, get everything back down/up, manage a maintenance plan and assume that it’s not affected by radiation you need to make it cheap enough to be profitable over fabs on the ground.bit_user said:Those are all engineering problems. Hard ones, but the first step is figuring out whether space truly offers advantages not available in terrestrial manufacturing. If not, then we can stop right here. If so, then the next step is to figure out all the issues around performing the full chipmaking process (or at least all of the stages that need to happen in orbit) and the logistics + scale-up problems you mention.

A skyhook is LEO only this really should be GEO as to not crash every few yearsbit_user said:

Someone mentioned that an Orbital Skyhook is much more practical than a space elevator and still a more efficient way to get stuff into orbit than launching every payload with all the propellant needed to get it into orbit.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Skyhook_(structure)

The problem with fully self-propelled launch vehicles is that the propellant needed for that last leg of the journey adds weight and must itself be lifted, as well as the additional fuel tank capacity needed to hold it. So, the benefits of launching to a suborbital altitude are nonlinear. -

bit_user Reply

Accounting is about moving money around. When you want to make something cheaper, that's still engineering.LordVile said:It’s not really an engineering problem it’s an accounting problem. If you do find a way to power it, get everything back down/up, manage a maintenance plan and assume that it’s not affected by radiation you need to make it cheap enough to be profitable over fabs on the ground.

Think about bridges. You need a bridge to be strong enough to hold its required carrying capacity and durable enough to last for its design life. You don't want to over-build it by too much, or else the materials and construction costs needlessly balloon. So, engineering is required to find better materials and designs to deliver on its requirements within budget. Engineering.

Those aren't the only two orbital altitudes. You don't need to go all the way up to a geostationary orbit, just to achieve a low rate of decay.LordVile said:A skyhook is LEO only this really should be GEO as to not crash every few years

Also, I think Skyhook can work even to help lift to higher orbits. It just means that you need to carry some fuel with you, beyond the skyhook stage. -

George³ By the way, it is interesting to what extent the purity and defect-freeness of semiconductors manufactured in orbit would contribute to increasing the performance and reliability of chips, since they are already close to the physical limits of miniaturization? Even if they were manufactured perfectly, which is questionable in space due to radiation, electromagnetic interference, etc., despite the improvements mentioned in the article, they cannot overcome the physical limits.Reply -

George³ Reply

And higher orbits, especially geostationary, will require crossing the Van Allen belts...bit_user said:Accounting is about moving money around. When you want to make something cheaper, that's still engineering.

Think about bridges. You need a bridge to be strong enough to hold its required carrying capacity and durable enough to last for its design life. You don't want to over-build it by too much, or else the materials and construction costs needlessly balloon. So, engineering is required to find better materials and designs to deliver on its requirements within budget. Engineering.

Those aren't the only two orbital altitudes. You don't need to go all the way up to a geostationary orbit, just to achieve a low rate of decay.

Also, I think Skyhook can work even to help lift to higher orbits. It just means that you need to carry some fuel with you, beyond the skyhook stage. -

LordVile Reply

It depends IF it’s possible to get it that cheap. You can engineer something to be as cheap as possible and it can still be economically unviable.bit_user said:Accounting is about moving money around. When you want to make something cheaper, that's still engineering.

Think about bridges. You need a bridge to be strong enough to hold its required carrying capacity and durable enough to last for its design life. You don't want to over-build it by too much, or else the materials and construction costs needlessly balloon. So, engineering is required to find better materials and designs to deliver on its requirements within budget. Engineering.

You’re going to be launching billions in value of equipment, a low rate of decay isn’t going to be profitable unless you operate it like the ISS which increases cost over time.bit_user said:

Those aren't the only two orbital altitudes. You don't need to go all the way up to a geostationary orbit, just to achieve a low rate of decay.

The extra fuel you’d be carrying to get up normally you mean?bit_user said:

Also, I think Skyhook can work even to help lift to higher orbits. It just means that you need to carry some fuel with you, beyond the skyhook stage. -

bit_user Reply

Heh, the maintenance costs of just about everything increase over time, as more and more parts of it degrade and need repair or replacement.LordVile said:You’re going to be launching billions in value of equipment, a low rate of decay isn’t going to be profitable unless you operate it like the ISS which increases cost over time.

Well, if you want to look at the question seriously, then Wikipedia says (in the page I previously linked) a skyhook design was proposed that could reach altitudes of up to 700 km. 600 km is about the point at which atmospheric density drops to that of space. It's atmospheric drag that makes lower orbits less viable, which is probably why the skyhook proposal targeted 610 to 700 km.LordVile said:The extra fuel you’d be carrying to get up normally you mean?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thermosphere